How Does CASB Support the Secure Edge and SASE?

Cloud access security brokers (CASBs) are part of a security framework that has evolved with the migration to cloud environments.

This migration has led to a unification of networking and security functions, accompanied by a growing reliance on the use of public cloud applications via remote access. That trend in turn has revealed the limitations of traditional application protection strategies. Lots of application activity can slip through the cracks if users and endpoint devices rely on centralized security based on IP addresses. And network performance suffers as traffic must be backhauled to grant users access.

CASBs, or cloud access security brokers, are part of the solution. As the name implies, these cloud-native services govern, or broker, traffic between end users and endpoint devices in order to maintain security and keep watch for rogue application activity.

Since CASBs work with distributed, cloud-based applications, they form one aspect of the secure edge or secure access service edge (SASE) -- the model for today’s distributed virtual networks. So vendors of CASB also offer other security functions, either through their own product integrations or via partnerships with other suppliers.

CASBs also can be included or integrated with solutions based on software-defined wide-area networking (SD-WAN). In this way, they serve the basic structure of the secure edge, which works best from a cloud-native SD-WAN platform.

What CASBs Do

CASBs began to emerge nearly a decade ago, and over time have come to be qualified by performing the following functions for securing access to and from cloud applications:

- Providing visibility into who is using which cloud services on a network;

- Controlling access to those cloud services by blocking unauthorized users or endpoints;

- Assessing the behavior of users and endpoints to enforce real-time access control of cloud services;

- Reporting on how well cloud services meet data residency and compliance requirements.

But, as noted earlier, CASBs aren’t limited to these tasks. In addition to being part of broader SASE and secure edge solutions, most CASBs come with additional security functions such as zero-day threat protection, secure Web gateways (SWGs), data loss prevention (DLP), and zero trust network access (ZTNA). Some feature encryption, and many offer remote browser isolation (RBI), in which browsing activity is cordoned off from any underlying device.

How CASBs Work

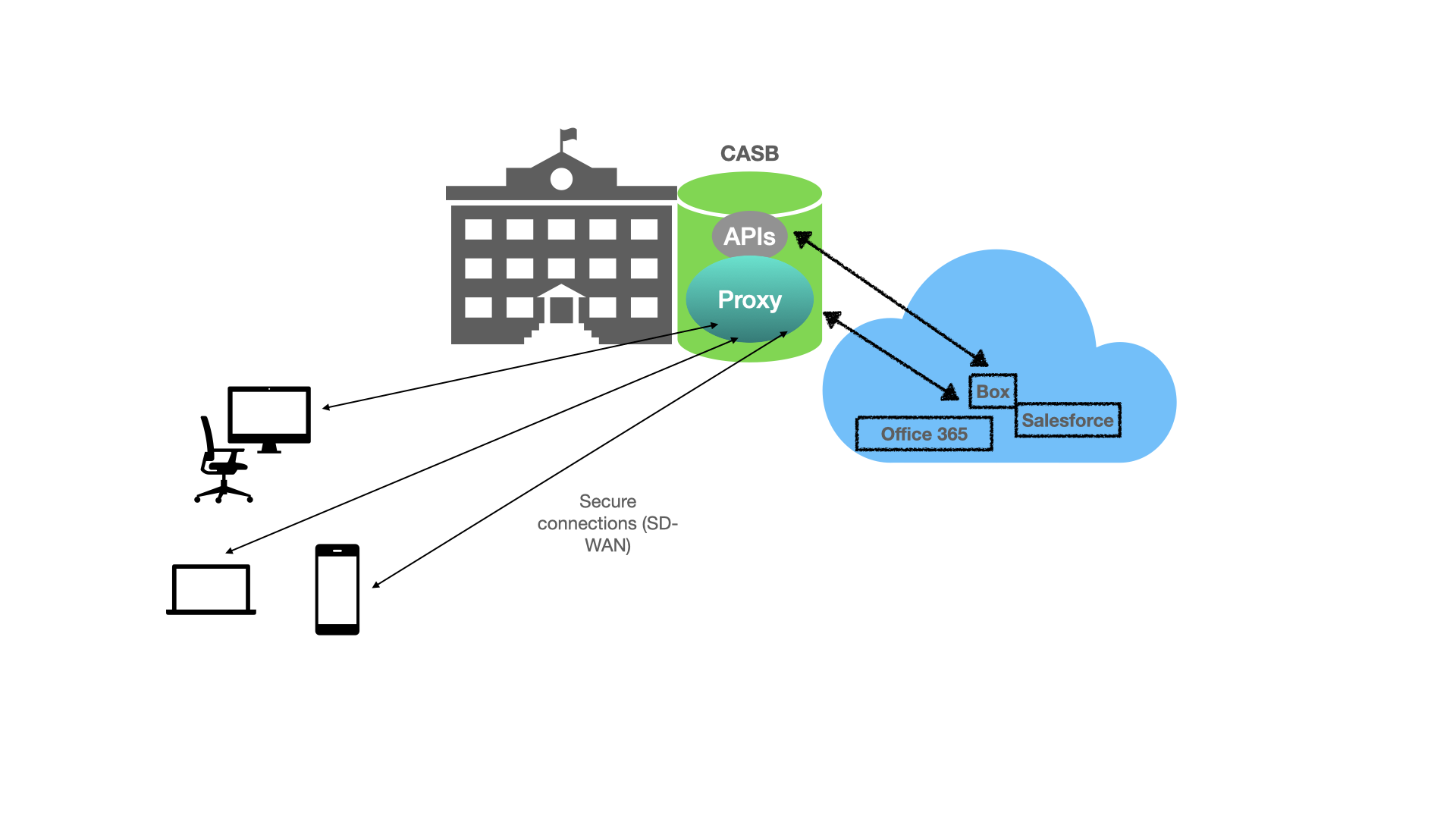

CASBs achieve their broker goals by establishing proxies between users and public or private cloud services, in some cases through points of presence (PoPs) set up at specific edge locations. Code can be loaded into browsers or agents deployed on users’ laptops or other devices to enable cloud application users to interact with the CASB, as indicated in the diagram below:

Source: Futuriom

There are many technical arguments about the various ways CASBs are implemented in vendor solutions. These days, most systems deploy some combination of proxy networking -- forward, in which traffic is checked on its way into the application; or reverse, in which all traffic is checked as it leaves the app. In both types of proxying, identity management techniques such as secure single sign-on are deployed within the CASB or through an integrated solution that works with it. These proxy methods can also be combined with application programming interfaces (APIs) for specific cloud-based apps, such as Office 365 or Salesforce, in order to check traffic patterns and take action to enforce security policies specific to those apps.

While there are pros and cons to the various CASB implementations, a couple of functions seem universally important. First, these days CASBs are typically implemented in the form of cloud services, which can be more easily — and cost effectively — adapted to secure edge implementations than solutions based on single-vendor services or hardware.

A second important CASB feature is the ability to grant access to cloud applications based on identity and context within the corporate environment, not solely on IP address. So CASBs can identify users by location, device, name, and other features, and control their access to specific apps based on that information. This is a more comprehensive and effective approach than filtering only by IP address.

Who Makes CASBs

As CASB functions are merged into other kinds of security and secure edge solutions, companies that specialize in this technology have been acquired by larger players eager to add CASB to their services. Cisco (CSCO), for instance, acquired CASB capabilities with its purchase of Cloudlock in 2016; Forcepoint via the Skyfence portion of Imperva, acquired in 2017; McAfee (MCFE) via Skyhigh Networks in 2018 — to name just three examples.

As of this writing, independent CASB vendors include Bitglass, CipherCloud, and Netskope — all late-stage startups with substantial assets and valuations. Netskope, for instance, as of early 2020 had $740 million in funding on a valuation exceeding $3 billion. Perhaps it’s not unrealistic to imagine an exit via IPO or acquisition by a major player.

Besides Cisco, Forcepoint, and McAfee, CASB suppliers who’ve acquired or created their own solutions include Microsoft (MSFT), Palo Alto Networks (PANW), Proofpoint (PFPT), and Symantec (SYMC). In all of these cases, CASB has been subsumed into a branded raft of integrated security solutions — such as the Cisco Umbrella — highlighting CASB’s role as a partial solution to augment a series of other functions.

The Future of CASB

As noted, CASB adds security to a broad spectrum of solutions that are required to secure remote access and protect the network edge. The move to cloud native environments ensures CASB will maintain this role. Expect to see more consolidation as larger vendors continue to reach out and pay handsomely for CASB technology to augment their edge solutions.