The Building Battle in Data Center Chips

There’s a war on in data center chips. For over a year, the major chip suppliers — including Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) and Intel (INTC) — have increased competition and innovation in the data center space. Against a backdrop of supply chain shortages and delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, they’ve responded to demand from cloud hyperscalers with designs that boost data center capacity and performance.

Data Center Top Rivals: AMD Vs. Intel

Central to the data center chip war is the rivalry between Intel and AMD. So far this year, AMD seems to be gaining momentum while Intel has stumbled, despite maintaining its dominant market share.

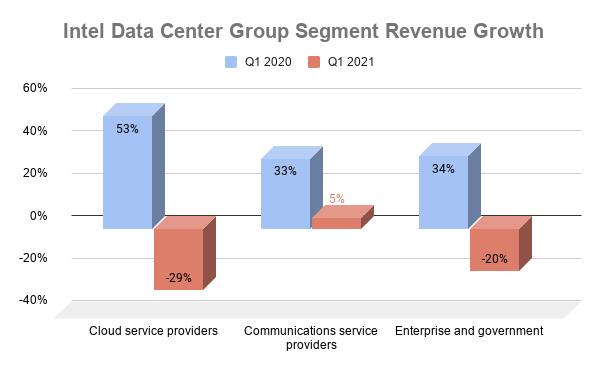

When Intel released Q1 2021 quarterly earnings on April 22, 2021, it revealed a disconcerting 20% drop year-over-year for its Data Center Group chips. That segment showed $5.6 billion in revenue, roughly 30% of overall quarterly revenue, compared with $7 billion for last year’s quarter, which represented 35% of total Q1 2020 revenue.

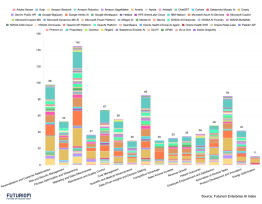

Most distressing to observers was the drop in sales to cloud service providers, as shown in the chart below:

Source: Futuriom, from Intel financial reports

Meanwhile, when AMD announced quarterly earnings on April 27, the company’s Enterprise, Embedded, and Semi-Custom (EESC) segment, which contains its data center processors, showed whopping 286% growth year-over-year. In all, the segment scored $1.35 billion in revenue, nearly 40% of the $3.45 billion overall quarterly revenue.

Why Is AMD Soaring Past Intel?

There are several reasons why AMD seems to be outstripping Intel in the data center. The first is AMD’s manufacturing stance. Instead of building its own chips, as Intel has done, AMD benefits from tight "just in time"-style production arrangements with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.

It was this manufacturing advantage that helped get AMD’s next-generation EPYC data center processor — the “Milan” chip — into the hands of cloud providers, while Intel struggled with delays in the launch of its latest high-end data center CPU, codenamed Ice Lake.

Intel is working hard to boost its manufacturing capabilities. The company plans to spend $20 billion on two chip plants in Arizona; it has upgraded manufacturing in New Mexico, and is reportedly expanding R&D in Israel, among other projects.

Intel executives also attributed the recent drop in data center sales to a “challenging compare” against last year’s quarter and a period of “digestion” by cloud service providers.

“We had an extraordinary last year, and now customers are almost through the digestion of that, and we're starting to see signs that they want to start the next build phase in their cloud,” said Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger on an earnings conference call with analysts.

But AMD stresses its head start. “We expect the number of AMD-powered instances to double by the end of the year to 400 as Microsoft Azure, Amazon, Google, IBM, Oracle, and Tencent significantly expand their offerings with third-gen EPYC processors,” said AMD CEO Lisa Su on the earnings call.

AMD CEO Lisa Su. Source: AMD

The Role of Arm and NVIDIA in Data Center Chips

The war between Intel and AMD has been complicated by another adversary — NVIDIA (NVDA) and its would-be acquisition, Arm Holdings, now owned by SoftBank. After several months of record growth in sales of accelerator and artificial intelligence (AI) chips to high-performance computing (HPC) customers, NVIDIA last month unveiled its first CPU chip, codenamed Grace.

Based on CPU cores from Arm, the Grace chip is geared specifically to HPC and AI applications. But given the demand for those functions in hyperscale data centers, it probably won’t be long before Grace is taken up by cloud providers and their suppliers and enterprise customers.

Still, Grace won’t be generally available until 2023. Meanwhile, NVIDIA’s $40 billion proposed buy of Arm continues to suffer objections from competitors and regulators. A top concern is that NVIDIA’s ownership of Arm would result in preferential treatment of NVIDIA. Some sources complain that parts of the Grace chip were provided by Arm exclusively to NVIDIA in violation of Arm’s democratic ecosystem charter.

Google, Others Grow Their Own Data Center Chips

Worries over Arm aren't misguided. While Intel and AMD duke it out with each other and NVIDIA, the cloud hyperscalers they rely on have branched out on their own, using their extensive resources to commission chips based on Arm licenses.

Amazon (AMZ)’s AWS, Microsoft (MSFT)’s Azure, and others run proprietary components, many from Arm. There’s AWS Graviton2 processors, developed with Arm technology, to improve the performance of EC2 instances. Azure’s Sphere chips, developed in part with Arm components, support Internet of Things (IoT) applications.

A Shifting Marketscape

There's plenty more activity in data center chips. Last month, for instance, Google unveiled a so-called video coding unit (VCU) to improve the performance of video in services such as YouTube. Google also offers a Tensor Processing Unit (TPU) for use in supercomputing services on Google Cloud. And Facebook reportedly plans to launch its own chip design center in Israel.

All of which adds to the many open questions in the data center chip market, which will only proliferate as 5G, multi-cloud environments, and the network edge gain importance with cloud and enterprise customers worldwide. The war in data center chips could become a full-blown revolution.